BACK ISSUE

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ

AND DOWNLOAD

- Gems of Truth by Stan Schmidt

- Where In the World Is God? by Alec Brooks

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org or send it by regular mail to:

6820 Auto Club Road #320

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA

- Your articles and booklength reports should be written, preferably, following the MLA Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics, and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2001

M. S. Thirumalai

ANCESTOR WORSHIP IN CHINA

Noah Krieg

1. ANCESTOR WORSHIP - BONDAGE OF FEAR AND UNCERTAINTY

The practice of ancestor worship in China, based on long-held beliefs of spirits of royalty and family, has survived many centuries, beginning with the time of the Emperors. This religious practice has held many Chinese in the bondage of fear and uncertainty, as sacrifice and divination alone serve as the foundation for success for the living. While complex in practice, the fundamental idea of ancestor worship is fairly simple.

2. AN ANCIENT PRACTICE STILL IN VOGUE

Though there is no precise date for the beginning of ancestor worship in China, it is clear that it was prevalent even during the time of the first Emperors. The Emperor was powerful on earth, and the belief holds that he must be powerful in the afterlife as well. While the Emperor's body dies, his spirit lives on, and thus "the deceased Emperor still exercises authority, but over a realm of spirits." In this, the Emperor may be a judge in a judicial assembly composed of other spirits, for example. Because the man held such a high position in his earthly, physical environment, he "cannot be relegated to immediate obscurity or unemployment in the post-mortem state" (Walshe 728).

3. HEAVENLY ORIGIN OF HUMANKIND

The foundation of ancestor worship also rests in the belief that humankind has the heavenly origin. Thus, the Emperor, because he was the highest rank among humans, took the title "Son of Heaven," a rank instantly worthy of veneration in the afterlife. It is said that the Emperor's ancestors should occupy a place at the court of the Supreme Being, and whose line can be traced to conjunction with the Deity. Not only were early Emperors identified as children of Heaven, even later Emperors and sages were associated with deity, as they were called "Associate of Heaven." This title carried connotations not only of direct descent from the Deity, "but also the fact that life-work of such worthies was a fulfilment of the Divine will -- they were 'fellow-workers with God'" (Walshe 728).

4. A CHIEF FUNCTION OF ANCESTOR WORSHIP

Because of this, their work was not brought to a halt when they passed into the afterlife, but they were still thought to be fellow-workers with the Heaven in administrating and superintending the world. Walshe gives the example of Yen-lo, who was "originally a just and perspicacious judge," who came to hold a position as judge of the infernal regions after death. He eventually became the god of Hades (729). In modern times, ancestor worship may be performed to invoke the dead to "discharge those duties which were practiced in life: giving sanction to a marriage and family division and acting as a disciplinarian for he younger generations" (Thirumalai 128).

5. REVERTED TO HEAVEN: AFTER-LIFE

The ideas about the spirit world are based upon the belief that, not unlike the ancient Hebrew view, Ching notes, there is a "heaven above, the abode of the dead below, and the earth, the abode of the living, in between" (15). Every person has a body and a spirit, as we have seen from the ancient Emperors, and when that person dies, his body decays while his spirit goes to the spirit world. Because humans are believed to have heavenly origins, when they die the term "reverted to heaven" is used (Walshe 728). The spirit of the dead will cross from the "bright" world of life to the "dark" world.

In this process, the spirit will be directed according to his deeds on earth. When he crosses the "boundary line" into the spirit world, he will be ushered onto one of two roads: one will lead to the Higher World, and one will lead to the Lower World. The spirit will follow the upper road that leads to the Higher World if the deceased was morally righteous and his life was filled with good deeds. In this he will be praised and honored by the ghostly judges and led into the Higher World or the Western World, where he will enjoy paradise under the rule of the Supreme Being (Thirumalai 126). In the Higher World, as was noted previously, the spirit will exercise administrative authority as assigned by the current spirit sages.

In contrast, if the deceased was not widely known for good deeds or uprightness or was blatantly immoral, the spirit will be judged according to his actions by the authorities standing guard at the gate on the road leading to the Lower World. Ten judges determine the next step in condemning the spirit, and the punishment for misbehavior in life ranges from a forced view of the spirit's former home town to torture and chains (Thirumalai 125). Pang suggests that this treatment is in line with the Chinese philosophy, for "central to traditional Chinese thinking is the sense of continuity. Thus, not only should one 'live and upright life,' one must also 'win good reputation after death'" (75).

6. JUDGMENT UPON THE SPIRITS

Much of the judgment upon the spirits of the dead is based upon social politics and filial piety. The actions required of people (and thus their standard for judgment) depended heavily on their social class. The Emperor was expected "to be a concrete example to all his subjects in his personal conduct." Pang describes that "the Chinese believed in two ways of teaching: by word and by personal example . . . Of the two, teaching by example is often considered to be far more effective and is thus given greater weight" (78).

Feudal princes were the real governors of the nation, so their assessment is based upon their success or failure to carry out the responsibilities of the state, namely, "to protect his country and further the welfare of his people" (Chen 18).

The high officers are the next social class. Along with loyalty to the Emperor, "their filial duty must be directed towards family welfare, offering sacrifices to their ancestors" (Pang 78). Their responsibilities of command and duty must be carried out well if they are to be honored in the next world.

The literary class is expected to serve the government as minor officers. Along with their governmental duties come filial duties as well. These allegiances are directed first to the parents, thought the father is honored more than the mother. The filial duty was also viewed in relation to their superiors, to whom they must show love and respect. We see that "while filial piety began at home with honouring parents, it was expected to extend outward and upward socio-politically for the well-being of all" (Pang 79).

Finally, the class of common people are assigned their duty and standard for judgement in the afterlife. The common people are required to "do the necessary in every season (such as growing crops in spring and reaping harvest in autumn), to do the utmost to make lands as fertile as possible, and to be frugal in their expense, in order to keep their parents in comfort" (Pang 79). We can see, then how this standard, along with the standards from the Emperor downwards, is measured heavily upon behavior in social and filial politics. As in the world of the living, there are classes and is a hierarchy in the spirit world, generally based upon how much attention is given to those spirits.

7. FAR MORE SPIRITS OF THE DEAD THAN THE LIVING DESCENDANTS!

There are far more spirits of the dead than there are living descendants or hours in the day to be able to recognize all of these. So, not all spirits can be worshiped by all people at the same time. We have seen that the spirits that are rewarded are gifted with greater power than they had on earth and are assigned to positions in the Higher World, but much of their place in that world has to do with their veneration by their descendants. A spirit may lose his place of authority and influence if it is forgotten by its descendants. The same principle is true of the Lower World-"the punishment suffered by a spirit in the Lower World may be mitigated or increased, respectively, by the good deeds or misdoings of its descendants" (Hsu 146).

Walshe depicts the same belief concerning spiritual hierarchy: "Their position depends, in the majority of cases, upon the influence which their earthly representatives are able to exert in the world of men" (729).

8. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE DYNASTIES IN THE SPIRIT WORLD

The Chinese have devised a system that rests upon the thought of the dynasties of old. Like the way Emperors and dynasties gave way to each other as one would fall and another rise, so the spirits operated in that "the ancestors of a dynasty which has come to an end are replaced in the highest positions of dignity by those of the new line of rulers."

This idea has been brought down to the basic family level as well, and the system of ancestor worship becomes like a banquet to which guests are invited. The more recently deceased ancestors hold places of honor at the banquet of veneration, especially the last three generations. The three generations are given special attention, and while the other ancestors may be worshiped at the larger ceremonies, they are not viewed as being the chief guests of the banquet (Walshe 729). Because spirits are so highly influenced by the actions of the living descendants, we can see the importance of the descendants' responsibility. As noted earlier, much of the influence they have on the spirit world depends on their loyalty in sacrifice.

9. SACRIFICE TO THE ANCESTORS

The history of sacrifice goes back to the imperial dynasties, and the Ancestral Temple is known to exist in the earliest ages of Chinese history. Emperor Shun (2255-2205 B.C.) was mentioned as worshiping in the Temple of the Accomplished Ancestors as he prepared to assume the throne of Yao. The historical record notes that Shun is said to have also "sacrificed with purity and reverence to the six Honoured Ones," who, Walshe explains, "probably represent his own ancestors to the third generation preceding, and those of Yao his predecessor, who had adopted him as a son and successor, and whose ancestors were therefore bracketed with his own" (729). There are also several other instances noted in which the new ruler was brought before the deceased body of the old ruler and proceeded to make sacrifices, all before 1000 B.C. Sacrifice, then, is historically based. The methods of sacrifice, however, will vary.

Ching gives insight into this, stating that "the Chinese word sacrifice is said to derive from a graph representing the offering of meat . . . to some spirit" (15). By this we know that the practice of sacrifice originally had to do with providing food for the dead. As time has progressed, sacrifice has become "an elaborate system of state sacrifices, each with its own name, offered to heavenly and earthly deities as well as to ancestral spirits" (Ching 15).

10. SACRIFICES

Traditionally, the sacrifices made in Chinese culture had to do with the killing of cattle, goats, and pigs. Young bulls were used for special occasions and the most important sacrifices. The animal had to be unblemished, and it was killed and opened up by priests. Many preparations were made to accommodate the dead animal, and "the fat was burnt to make smoke inviting the sprits to descend, and the internal organs were prepared and cooked" (Ching 16). Walshe also reports the use of jade, silk, and fruit in ancient sacrifices. More modern sacrifices are slightly different but include a similar method of sacrifice.

Hsu describes the sacrificial aspect of the trip to the graveyard and the items it includes. He begins, "they and a pack mule carried the foodstuff, pots and pans, blankets, kindling, and articles necessary for ritual offering." Continuing, he describes the offerings, "All the dishes prepared . . . were neatly arranged before the two main tombs . . . The family head then took some burning incense and wine and made a ceremonial offering . . . as he did so, paper money was burned" (182). Here we see some of the materials used in the modern sacrifices. These sacrifices must be performed on certain days, as specified by tradition.

11. TIMES OF SACRIFICES

Traditional Chinese text outlines that "In spring and autumn, they (the filial king Wu and Duke Chau) repaired and beautified the temple-halls of their fathers, set for their ancestral vessels, displayed their various robes, and presented the offerings of the several seasons . . . thus they (the filial sons) served the dead as they would have served them alive" (quoted in Chew 49). To this day, spring and autumn serve as the principal time for the offering of sacrifice. The days to sacrifice are very strict and specific, however.

Sacrifices to ancestors must occur on the first, third and fifteenth of the first moon; the sixth of April; the fifth of the fifth moon; the fifteenth of the seventh moon; the fifteenth of the eighth moon; the first of the tenth moon; on the last day of the year; on special occasions, such as weddings, etc. There is even a special festival held on the 15th of the 7th moon "for the benefit of the hungry ghosts who have no descendants to sacrifice to them; and the customary offerings are made to them on the part of the people generally" (Walshe 731).

12. LACK OF PIETY

The nature of exactness of such sacrifices, in special times and dates as well as in materials used for the process, leads one to believe that the Chinese worshipers are extremely pious. The opposite is often true. Chinese classical literature states that the real value of the sacrifice will be judged by the heart of the person who offers it. Thus, all the offering of food, which the offerer himself eats, and the paper money, etc., which benefit none but the manufacturer and retailer of such items, mean nothing without giving these things in a good spirit. Walshe suggests that "no doubt in early times the ideas of communion with the spirits of the dead was a powerful motive in the offering of sacrifices, . . but in the popular observances of ancestor worship, selfish considerations are not altogether absent" (731).

13. DEGRADATION

Sacrifice to the dead has degraded in theory in China. Walshe points out that "the manufacture of paper articles, for transmission to the dead by means fo burning, affords employment for millions of people; in some cities the beating out of tinfoil, and fixing it to sheets of paper, to be afterwards shaped into imitation dollars . . . is the staple industry" (731). Burning fake money is not very selfless, though this only begins to tell of the selfish motivations that drive sacrificial ancestor worship.

14. OTHER DRIVING FORCES

Hsu goes into great detail describing the dividing up of ancestral property and how this serves as a driving force for the participation in ancestral rituals: "when a family is divided, each new group is registered on the police register as a separate household; each new household has its own family altar . . . the property is managed . . . when a ceremony takes place" (114).

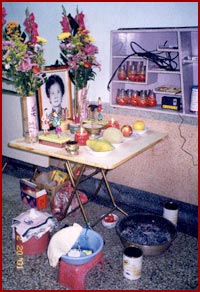

Another ulterior motive for sacrificial rites has to do with social convention. The person sacrificing to the ancestors must make as good a show as possible for his friends and neighbors. In most offerings where many are present, "all such relatives will be entertained at tea or dinner" (Hsu 115). All of these people in the community or in close relation to the family will meet around the shrine which holds the ancestral tablet, no doubt noting the level of ostentatious display for the ancestors.

The ancestral tablet is the not the home of the spirit, as is commonly mistaken. When sacrifices are made at this piece of wood (which contains the character inscriptions of the name and other relevant information of the deceased), the spirit is thought to then come to the "throne." The spirit will vacate the tablet as soon as the sacrifice is finished, however. Although heaven is their home, the spirits may come and go at will. Their precise location at any given time is unknown, however, "they may be present when the ancestral rites are being performed, occupying the 'spirit throne' or 'ancestral tablet,' but of this the celebrant cannot be assured; his duty is to act as if they were actually and consciously present, though no tangible indication be afforded him" (Walshe 729).

15. DIVINATION AND ANCESTOR WORSHIP

The ancestral tablet is not present for sacrifice alone, but along with sacrifice comes the second practice of ancestor worship: divination.

Divination may be defined as the ability, "based on extrasensory perception, to make pronouncements about the hidden future or events and relations of the present using different means (on which, by contrast, the pure 'seer' is not dependent)" (Küng 43). This practice is not unique to Chinese culture, and was not even originated in this area of the world, but divination is common to most cultures. In all cultures we find the ubiquitous human desire for the meaning of life, the secrets of fate and the future, answers to the indefinite questions of daily circumstance, to uncover the cause of an illness, or to bring to justice the hidden guilty party. China has a long history of divination practice for many of these reasons.

Inhabitants of northern China in the late fourth millennium B.C. are the first known practitioners of divination by means of studying the features of animal shoulder blades. This method included heating the bones and interpreting the cracks, colorations, etc., to determine what events would come to pass. Later historical records show that shells and bones of animals used in sacrifice were used for divinatory purposes. The assumption here was that "the dead animals would have special power in contacting others in the spiritual world, especially ancestor figures" (Ching 11).

Modern ancestor worshipers may perform such a practice with yarrow stalks, playing them like one would a deck of fortune-telling cards. This kind of divination is performed with little ecstatic behavior, and not usually for any specific traditional occasion. Another popular form of divination involves "inquiring of the dead by means of a ventriloquist in the person of a young girl, who, like the pythoness of Philippi, is supposed to reply on behalf of the deceased."

Mediums may also trace characters in the sand and communicate the intents of the spirits to the living by "a form of 'planchette,' consisting of a bent twig fastened to a cross piece which rest on the open palms of the medium's hands" (Walshe 731). These and different kinds of divination are commonly, though not exclusively, utilized in the cases of marriages and funerals.

16. DIVINATION AND MARRIAGE

Diviners, says Hsu, are important to all marriages because without such consultation, "the marriage hints of elopement," and "there will be no one to mediate in case of trouble or dissatisfaction" (85). Most diviners or marriages are men, and they are usually blind. The most common divination method for these professionals involves the examination of the "eight characters." This system is similar to a horoscope, and it reveals several different things, including the "suitability" of matches (Hsu 84). If the diviner does not satisfy the desires of the family, and they are determined to match the two they have in mind, there is always the choice to consult several diviners. These other diviners will most likely have reports that conflict with each other. However this is not done because the families involved do not trust the system of divination, "but they can always find something wrong with the diviner if he does not give the desired answer" (Hsu 85).

As the wedding proceeds, divination is used to determine the date and hour when the wedding will take place, "the exact moment of entry of the sedan chair into the house gate, the direction which the bride wis to face when first entering and sitting in her room, and so forth. All these have to do with the future success of the married life" (Hsu 92). Before the birth of the first child, the pregnant mother will consult a diviner to determine the name of the baby. This name will be the baby's name used at home, which will ensure the protection of the baby from evil spirits and illness (Hsu 201).

17. FUNERALS AND DIVINATION

Funerals are also an important item of concern for divination in ancestor worship. First, the grave site must be chosen. Diviners are employed in an important business called feng-shui, which means "wind-water." This practice is "closely connected with the subject of communion with the dead, one chief object being the selection of suitable grave-sites, where the dead may be expected to rest in peace, and thus be in a favourable condition for friendly communication with the living" (Walshe 731). The diviner will decide upon the burial location, considering several factors, including years and months and directions. Hsu notes that "certain years and certain months of each year are more propitious for certain burial locations with reference to the family dwelling," and that of the eight directions (north, south, east, west, southeast, southwest, northeast, and northwest), "a diviner must decide which direction is auspicious" (157).

18. COMMUNICATION WITH THE DEAD

The desire for blessing and successful communication with the deceased is so strong that, for example, if a family's graveyard is situated on a slope southwest of the house and the diviner says that this location is not favorable for this particular family in this particular year, the family will move the coffin to a different place, where it will rest temporarily until a more propitious year, when they will bury it on the family graveyard slope, southwest of the house (Hsu 157).

19. TO CONCLUDE

So much of not only special occasions but daily life in China plays out according to the successful practice of ancestor worship. For centuries, the living have lived so as to insure a place for their spirits in the Higher World after death. They have relied upon sacrifice and divination to secure blessing and good fortune upon their lives and families, to venerate the dead, and to determine what steps they should take in the future. The practice of ancestor worship in China continues to hold the people who practice it-who often display false piety, but even those who do not-in bondage, for their lives are controlled by inconstant forces and the fear that lies behind them.

Ancestor worship and divination are condemned in the Word of God. Christians in China are waging a valiant battle to eradicate this practice. Let us pray for their success, even as we try to understand this age-old practice. The bondage will be broken only with the help of the Holy Spirit.

REFERENCES

- Hsu, Francis L. K. Under the Ancestor's Shadow: Kinship, Personality, and Social Mobility in China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1971.

- Küng, Hans and Julia Ching, eds. Christianity and Chinese Religions. New York: Doubleday, 1989.

- Ching, Julia. "The Religion of Antiquity: Chinese Perspectives." In Küng and Ching 3-31.

- Küng, Hans. "The Religion of Antiquity: A Christian Response." In Küng and Ching 33-58.

- Sng, Bobby E. K. and Choong Chee Pang, eds. Church and Culture: Singapore Context. Singapore: Graduates' Christian Fellowship, 1991.

- Chew, John. "Ancestral/Parental Ties in the Old Testament and the Possible Bearing on Filial Piety." In Sng and Pang 47-64.

- Pang, Choong Chee. "Filial Piety: Biblical and Classical Chinese Perspectives." In Sng and Pang 65-84.

- Thirumalai, M. S. Other Religions. Minneapolis: Bethany College of Missions, 1999.

- Walshe, W. G. "Communion With the Dead (Chinese)." Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Ed. James Hastings. Vol. 3. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1955. 12 vols.

- Xiao Jing. The Book of Filial Piety. Trans. Ivan Chen. New York: 1908.

*** *** ***

Songs of Gary Johnson: Reminded of His Goodness | A Heart After God | Where In the World Is God? | The Truth About Lying: Francine Rivers' Rahab | HOME PAGE | CURRENT ISSUE of the journal | CONTACT EDITOR

Noah Krieg

Bethany College of Missions

6820 Auto Club Road Suite C

Bloomington, MN 55438, USA

E-mail: bcom@bethfel.org. Please mark "Attention: Noah Krieg" in the subject line.