Prof. Randall Smith teaches theology, philosophy, and courses related to Modern Challenges to Christianity, at the University of Saint Thomas, Houston, Texas. He is a strong apologist for the Christian faith.

We invite you to support this ministry. Contributions in support of this Ministry are tax-deductible. Kindly send your support to

Bethany Fellowship International

6820 Auto Club Road, Suite A

Bloomington, MN 55438.

Please write Thirumalai's Ministry in the memo column.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ

AND DOWNLOAD

- THE LAW IS HOLY by Pastor Harold Brokke

- WORLD MISSIONS - A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

by Tom Shetler - LIVE A VICTORIOUS LIFE IN THE SHADOW OF THE CROSS! : INTERCESSION, WARFARE, AND DELIVERANCE

by Pastor Ted Hegre. - MISSING PIECES: THE INCOMPLETE GOSPEL by LeRoy Dugan

- LUTHER'S PROTEST by M. S. Thirumalai

- TELL ME IT'S TRUE ...

A Book Of Poems by Stan Schmidt - SOMETHING IS GREATER THAN WONDERS...

A Book Of Poems & Free Verses by Pastor Harold Brokke - GEMS OF TRUTH by Stan Schmidt

- WHERE IN THE WORLD IS GOD? by Alec Brooks

- LIGHT OF THE WORLD, an Original Screenplay by W. G. Orr

BACK ISSUES

- NOVEMBER 2001

- DECEMBER 2001

- JANUARY 2002

- FEBRUARY 2002

- MARCH 2002

- APRIL 2002

- MAY 2002

- DECEMBER 2002

- JANUARY 2003

- FEBRUARY 2003

- MARCH 2003

- APRIL 2003

- MAY 2003

- JUNE 2003

- JULY 2003

SEND YOUR ARTICLES FOR PUBLICATION IN Christian Literature and Living.

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org or send it by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

6820 Auto Club Road #320

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA - Your articles and booklength reports should be written, preferably, following the MLA Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics, and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2001

M. S. Thirumalai

SPEAKING OF LITURGICAL ARCHITECTURE

Modernism and Modern Church Architecture

Prof. Randall Smith

An Attractive Thesis

A common thesis which has gained some currency recently suggests that the reason church architecture is in such a state of disarray has largely to do with the misunderstandings that arose from the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Such seems to be the thesis, for example, of architect and author Steven J. Schloeder's widely discussed 1998 book Architecture in Communion. "I have undertaken this work," he says in his introduction, "because I find many - or rather most recent Catholic churches to be banal, uninspiring, and frequently even liturgically bizarre."1 What seems to be the source of the problem? "Since the promulgation of Sacrosanctum concilium in 1963," answers Mr. Schloeder,

there have been both widespread and obvious changes to the liturgy and consequent changes to the buildings in which the liturgy is celebrated. While the roots of these liturgical and architectural changes pre-date the Council by quite a few decades, the vast majority of Western Catholic churches built up to the time of Sacrosanctum concilium were rather traditional and formal.... Stylistic difference aside, until 1963, Catholic churches on the whole looked very much as they had for hundreds of years previously. The changes since Vatican II have been significant and almost universal.2The first chapter of his book is in fact titled, "An Architectural Response to Vatican II" and the whole of that chapter leads up to the last two sections, entitled, respectively: "The misinterpretation of Vatican II" and "The need for a reexamination and a fresh response." In this last section, Mr. Schloeder begins by asserting categorically: "These problems in the interpretation of the Council's documents have undoubtedly contributed to the confusion in the architectural ordering of churches."3 And one page later, he insists that:

The banality and architectural impotence of churches of the recent past [since 1963] cannot be attributed only to an increasingly secularized modern society, for societies have always had tensions between the sacred and spiritual and the secular and material; there has always been a conflict between the City of God and the City of Man. I believe that it is rather a lack of conviction and direction, brought about by theological confusion, that has resulted in liturgical and architectural poverty. 'The barrenness of the building reflects the barrenness of contemporary theology.'4Such a thesis is especially attractive, one has to admit, to those of us of a more "academic" bent, such as theologians and liturgists, because it suggests that the problem is one of ideas: art follows ideology. Correct the ideas - get the theology of the liturgy right (the job of, guess who?, theologians and liturgists) - and voilá, the architecture will take care of itself.

Now, as attractive as this thesis is, I'm afraid that its one drawback is that it's largely not true. The character of contemporary church architecture is not, I would suggest, primarily the result of bad ideas about liturgy - although, Lord knows, we have plenty of those. Rather, bad church architecture is the result, quite simply, of bad ideas about architecture. The problems of contemporary church architecture, in other words, weren't caused in the first place by the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council. No, they were caused primarily, I would argue, by the embrace of modernist architectural principles by contemporary architects and by the liturgical "experts" who have laid down the guidelines and regulations for all new church buildings.

An Interesting Counter-Example: Speaking of Liturgical Architecture

While there are many different historical examples that might be used to illustrate this thesis, for the purposes of this article, I would like to focus on one small, but particularly interesting example: a little booklet published in 1952 by the Liturgy Program at the University of Notre Dame called Speaking of Liturgical Architecture, written by one Fr. H. A. Reinhold - a man described in the book's foreword as someone who "needs no introduction to American Catholic readers," because, according to the writer, "he has become a household term [sic] in things liturgical."5 Although published in 1952, the lectures contained in this little tract were actually delivered several years earlier, during the summer of 1947, at the "first liturgical summer school at the University of Notre Dame."6 Considering the date of the original lectures (1947), it would seem something of a stretch to argue that Fr. Reinhold's ideas about liturgical architecture embodied that well-known bogeyman, the misbegotten "spirit of Vatican II," given that they were delivered some fifteen years before the Council!

The point of publishing the book, according to Fr. Mathis, writing in the book's foreword, was "to focus attention on some simple but basic liturgical requirements in the building and decoration of Catholic churches, requirements that are not generally known even by those who have the professional responsibility of constructing our houses of worship."7 Let me repeat that: "to focus attention on some simple but basic liturgical requirements in the building and decoration of Catholic churches" (emphasis mine). Indeed, this is the thesis that is repeated throughout the book: The rules for building churches must be derived from their liturgical function. "One thing it is safe to say," says Fr. Reinhold, "[a church's] liturgical, sacramental function ought to be the determining factor [in its design]." Of his approach to church architecture, he says very clearly: "We are trying to find a principle for our procedure in the liturgy itself." The title of the book, after all, is not Speaking of Church Architecture, but rather Speaking of Liturgical Architecture.

And here, I would suggest, is the crux of the matter. Here is where something very interesting starts to happen - interesting both conceptually and historically. What seems at first like a very innocent and perhaps even appropriate principle of church architecture - design the church with the liturgy in mind - can become in practice (and in fact did become, I would argue), something very different.

Form Follows Function

Take, for example, one of the major, bold-faced headings of Fr. Reinhold's text, which instructs the prospective student very prominently that the basic principle to be followed in building churches is: "Form follows function." Indeed, Fr. Reinhold's book starts out with a chapter entitled "Functional Characteristics," and he develops his notion of church architecture from this starting point.

Now, as most of the architecturally literate readers of this journal are probably already aware, the phrase, "Form follows function," was one of the rallying cries of Modernist architects and "functionalism" one of their most beloved principles of design. And although Fr. Reinhold denies repeatedly throughout his book that his is favoring any particular "style" of architecture over any other, yet he begins his discussion of church architecture (perhaps without being fully aware of it) from a distinctively modernist perspective. And this perspective - this starting point - radically affects everything else that follows.

Before we go on, though, it is important that we clarify what "form follows function" and "functionalism" means in this context. If "form follows function" meant simply that a building should fulfill its function, that is to say, the purpose for which it was built, that would scarcely be controversial, or indeed, even much worth mentioning. So, for example, it would be one thing to say that a church shouldn't have, say, a huge wall across the middle of the nave so that people can't walk down the central aisle, or that it shouldn't have its doors hidden so that no one can get in or out. But of course, if "form follows function" had meant that, it's hard to see how it could have become the rallying cry for a new architectural movement. "Build buildings so that they work" is not exactly a bold and daring new statement. Besides, modernist architects are notorious for not caring whether or not people can find the doors in their buildings, or whether or not they can get around comfortably in them.

For modernist architects, the phrase "form follows function" means something very different. Through a bizarre series of transformations that occurred after the first appearance of the phrase in the writings of famed Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, who considered it obvious that building design should indicate a building's functions and that, where the function does not change, the form should not change, the phrase "form follows function" was later taken up by Modernist theorists such as Mies van der Rohe and acquired a radical new meaning. The Columbia Encyclopedia, for example, describes "functionalism" as follows:

Functionalist architects and artists design utilitarian structures in which the interior program dictates the outward form, without regard to such traditional devices as axial symmetry and classical proportions. After World War I, the German Bauhaus produced a number of influential architects and designers, notably Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who worked within this aesthetic. Functionalism was subsequently absorbed into the International style as one of its guiding principles.8What does this mean concretely?

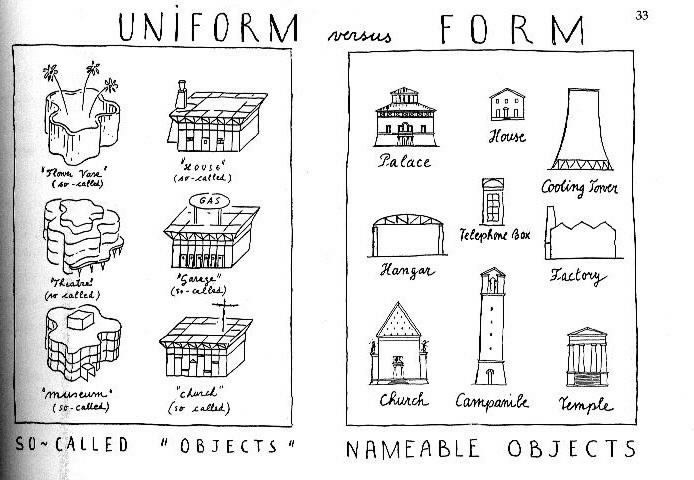

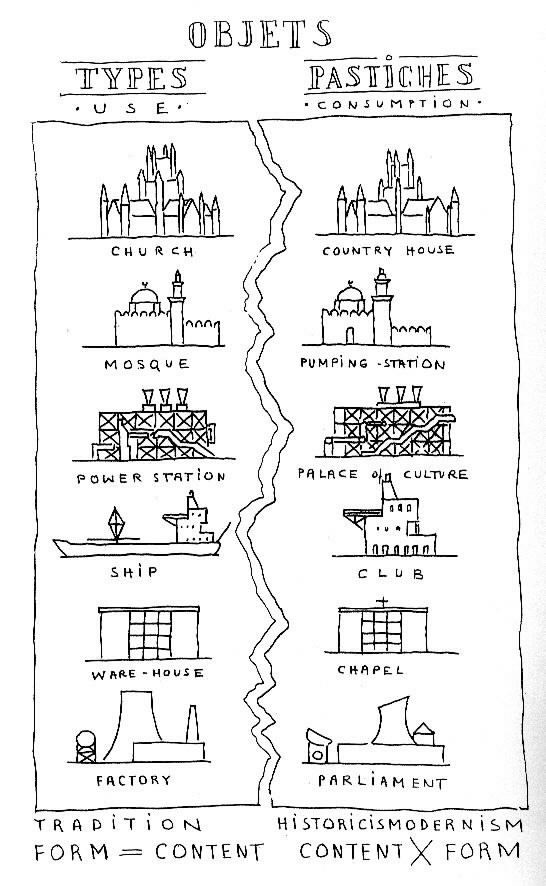

Well, one of the things is doesn't mean is this: that a building should "look" like what it is: that is, that a house should "look like" a house or that a bank should "look like" a bank. Indeed, it is precisely one of the most characteristic features of modernist architecture, according to its critics, that it obliterated the differences among building "types." As this drawing by architectural theorist Leon Krier suggests, we used to recognize a building from what it "looked" like, and we gave it a name because of its form. We called a certain building a "church" because it had the form of a church; another a "factory" because it had the form of a factory. Now, however, we call a building a "house," a "garage," or a "church," not because they have that form, but because they serve that function. Indeed, if we were to change the sign on the building, then the building changes: thus if we take the "bank" sign off the bank and put the "church" sign on, then it becomes a church.

In other words, the modernist notion of "function" does not pertain to the subjective desires or designs of the potential users of the building; no, rather "function" is an objective aesthetic category for which a certain objective "form" necessarily follows.

Who, then, can discern the "correct" aesthetic form necessary to this particular circumstance? Well, that's why you have to hire the Modernist architect (or some other expert intellectual): because he is the only person capable of such aesthetic, intellectual discernment - capable, in other words, of designing, not necessarily the building you would have wanted, but of designing the building you should have wanted. Rather than "form follows function" meaning that the form of the building - both its inside design and its outside design - should follow from the purpose for which the building serves (and indeed the purpose of a building's exterior may be very different from the building's interior), now "form follows function" means that the form of the building should embody a certain ideal "type."

Functionalism and the Principle of "Expressed Structure": Building from the Inside Out

We can perhaps best illustrate this sensibility by simply turning to Fr. Reinhold's book and showing what he means by "functionalism." Does he begin, for example, by considering, perhaps by using historical examples, what would make for a beautiful and excellent liturgical celebration? Perhaps things like spaciousness, a dynamic sense of space leading the eye upward, or beautiful stained-glass windows with biblical themes to instruct the faithful and to give them a foretaste of that heavenly banquet to which we are all being called in the mass? Well, not exactly. Rather he decides that, because baptism and the Eucharist are, as he says, "the two most important sacraments," therefore: "the prominence of these two sacraments must determine the architecture of a church, inside and out (I emphasize this)" [that's his emphasis, by the way, not mine]. "A parish church," says Fr. Reinhold, "is above all a Eucharist ... and Baptism ... church. Its inside should express this. If its inside organs are thus disposed and visibly emphasized, honest architecture (functionalism in its true sense) should manifest these two foci on the outside [as well] - in the right place."

With this, it becomes clear what "functionalism" means for Fr. Reinhold. "Functionalism," on this view, does not mean that the building should adequately facilitate its function: namely, liturgy. No, functionalism, "in its true sense," means "honesty" in architecture, and "honesty" in architecture involves expressing the inside of the building on the outside. This, of course, is Modernist architecture in its purest form. Indeed, in his best-selling book on Modernist architecture, entitled From Bauhaus to Our House, author Tom Wolfe describes in detail this fundamental Modernist principle of design:

Then there was the principle of 'expressed structure,' [among the Modernists].... Henceforth walls would be thin skins of glass or stucco.... Since walls were no longer used to support a building - steel and concrete or wooden skeletons now did that - it was dishonest to make walls look as chunky as a castle's. The inner structure, the machine-made parts, the mechanical rectangles, the modern soul of the building, must be expressed on the outside, completely free of applied decoration.Thus, for Modernist architects, it became essential that the outside of the building "reveal the structure" in an "honest" way. No longer would the outside of the building be allowed to "hide" the inside , for that would be "dishonest."

So it is not really liturgy that takes precedence for Fr. Reinhold - after all, effective and impressive liturgies had been going on in all sorts of different buildings for hundreds of years - no, what takes precedence is the form, the "idea," to which all buildings must conform, or be judged a failure. This is fundamental. We must begin with the disembodied Idea - with the language of pure Form - not with the living reality of what has actually been shown to work in practice, and then force everything to conform to that Idea. Indeed, perhaps nothing is more characteristic of the practice of contemporary liturgical experts than beginning, not with historical models, but with an idea of the "ideal" form, and then enforcing that form on the worshiping community, whether desired or not. The result, as often as not, is a "functionalism" that's not all that functional.

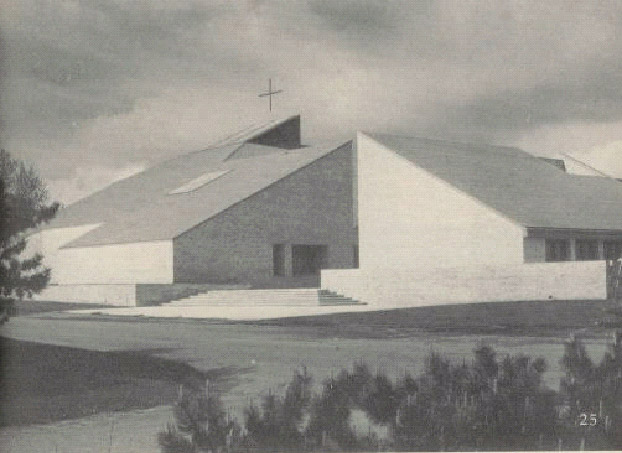

This is a view of architecture that designs buildings from the inside out. It is a view of architecture that sees the building as not much more than a "covering" or "skin" around a particular interior space.

The building or cover enclosing the architectural space is a shelter or "skin" for liturgical action. Its integrity, simplicity, and beauty, its physical location and landscaping should take into account the neighborhood, the city and area in which it is built.

Take, for example, this caption of a photograph, presented above, from the highly influential little book Environment and Art in Catholic Worship, which says, in part: "The building or cover enclosing the architectural space is a shelter or 'skin' for liturgical action." That comment, I would suggest, reflects a fundamentally Modernist notion of what a building is or should be. (And that building, I admit, makes me thankful that God didn't think of our skin as just a "cover" or "shell" for a certain bodily action. God knows what we'd look like. Indeed, isn't that one of the great things about skin: that it has a continuity and beauty all its own, not entirely unrelated to what goes on inside the body, but not entirely revelatory of it either?)

Functionalism as the Standard by Which to Judge the Failure of All Church Architecture of the Past

In any case, Fr. Reinhold's functionalist frame of mind is revealed, not only when he talks about modern churches, but when he comments on church architecture of the past as well. So, for example, the one thing that Fr. Reinhold admires about the Gothic style is the fact that the structure of the building is revealed externally. He says of the Gothic use of the flying buttress, for example, that: "The skeleton that was hidden in the Romanesque church has, [with the Gothic], grown out of its layers of skin and flesh, and man is turned inside out in his Gothic churches: he shows his interior .... This honesty in construction ... is something we begin again to love."

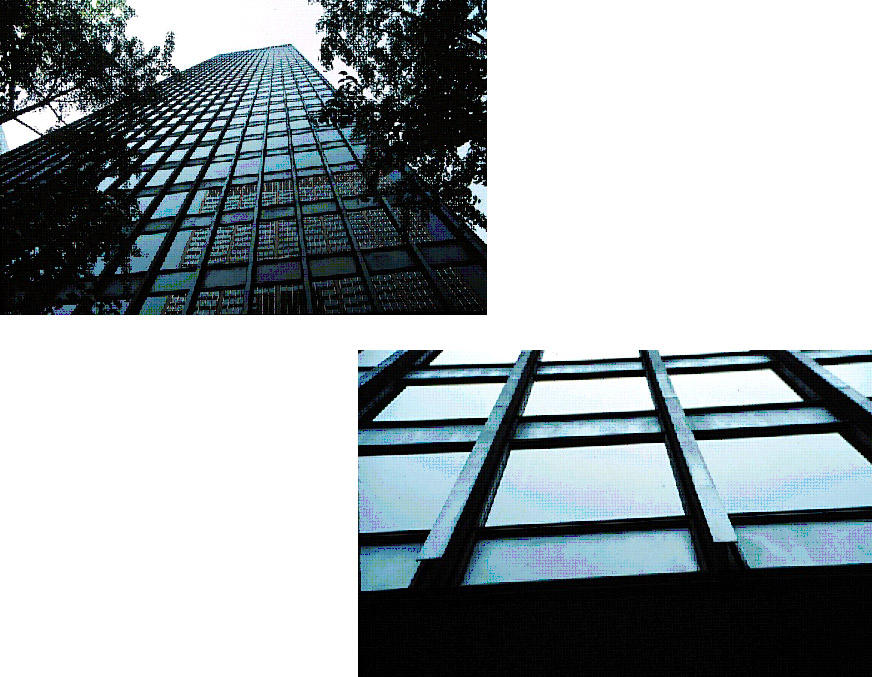

Now, who would the "we" be in that last sentence, do you suppose? Probably the same "we" who loved it when Mies van der Rohe expressed the structure "honestly" with black steel I-beams on the exterior of the Seagrams Building in New York City [See the visual below] - even though these exterior beams serve absolutely no structural purpose (so much for "honesty"!).

And this would be the same "we" who loved it when the Georges Pompidou center in Paris turned itself inside out, showing its interior exteriorly, in a structurally "honest" way.

It is undoubtedly this same "we" who would admire a Gothic cathedral like Chartres or Notre Dame, not because of its beautiful windows or its dynamic spaciousness, but because it reveals the interior structure exteriorly. That "we" is the "we" of Modernist architectural design.

Yes, Fr. Reinhold admires the Gothic's "structural honesty," but still, he finds it lacking as an example of proper liturgical architecture.

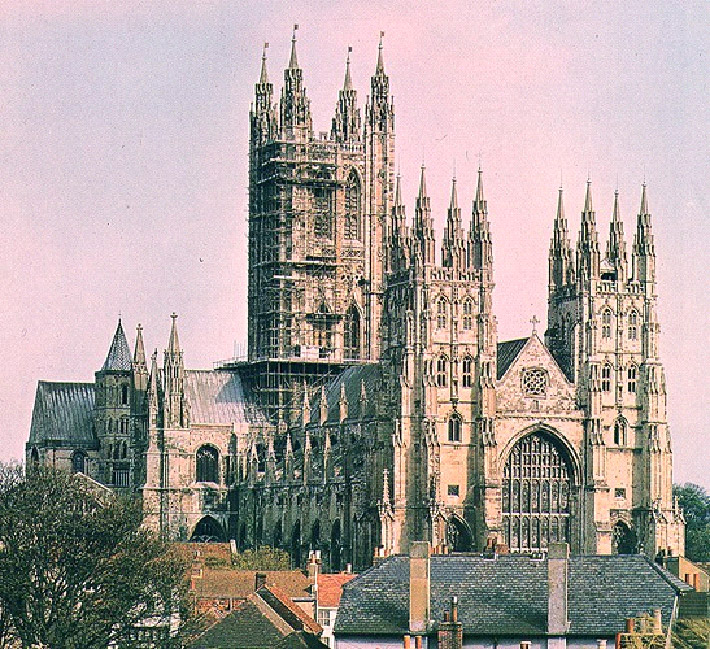

So, for example (see above), concerning the Gothic cathedrals of Canterbury, York, Fr. Reinhold says this:

The beautiful 'central' towers of Canterbury and York are a magnificent architectural accent, but have no liturgical, intrinsic function whatsoever. [Thus they fail, you see.] The spires of so many cathedrals, though lovely creations, create architectural emphasis around the comparatively insignificant bells - if anything. Even if you consider them as 'fingers pointing to heaven,' then the 'sermon in stone' or the architectural 'outcry of the redeemed' reaches its highest pitch at the gates, or straddles across the joining of the crossbeams in a cruciform church, [but are] unrelated to the internal organs ....

Ah yes, the great sin: external structure unrelated to the internal organs.

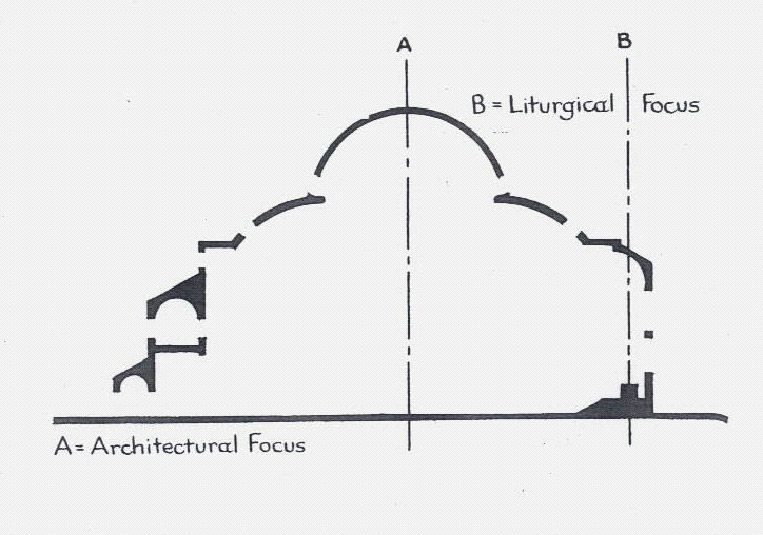

In fact, according to this principle, as it turns out, and as Fr. Reinhold plainly admits, almost all the great churches of Christendom have been architectural failures. Of the legendary Church of Holy Wisdom [See below] (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, for example, Fr. Reinhold insists that it suffers from the failure of having what he calls "misplaced accents," a failure he diagrams as follows:

Notice how the "architectural focus" (line A) and the "liturgical focus" (line B) are out of synch. This mustn't happen - something that the architects who built Hagia Sophia seem not to have considered.

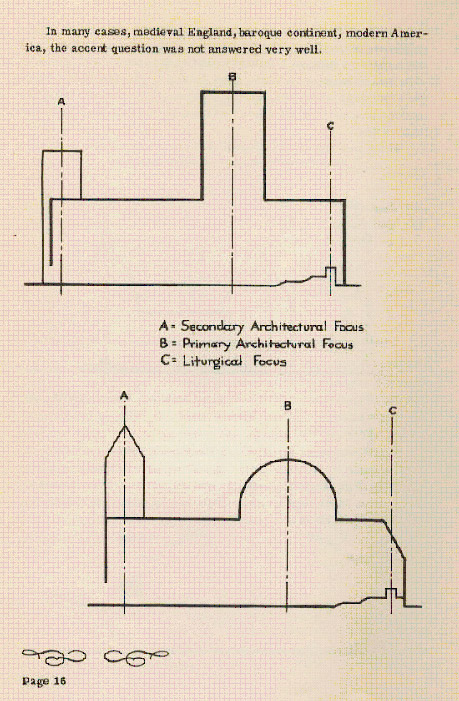

And indeed, this problem of "misplaced accents" besets, unfortunately, as it turns out, the majority of Western churches. [See below] "In many cases," says Fr. Reinhold, namely "medieval England, baroque continent, [and] modern American" [which, you have to admit, pretty much covers the spectrum] - in these churches, "the accent question was not answered very well." Notice again how line A doesn't line up with line B. This is not allowed.

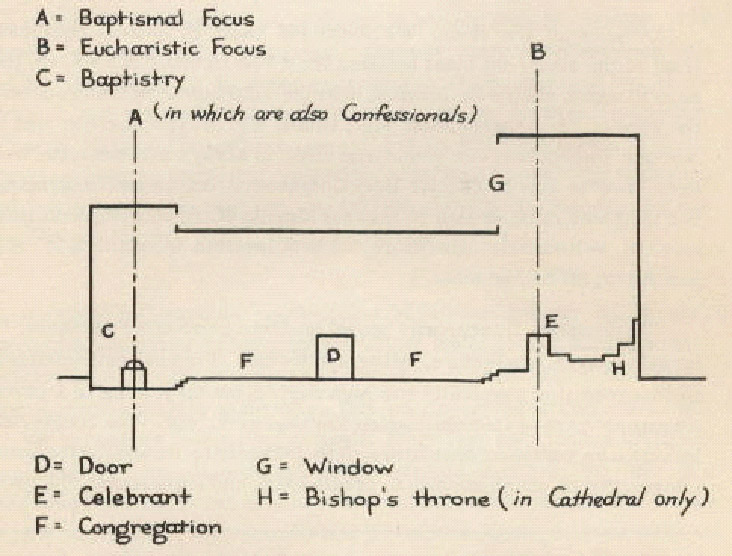

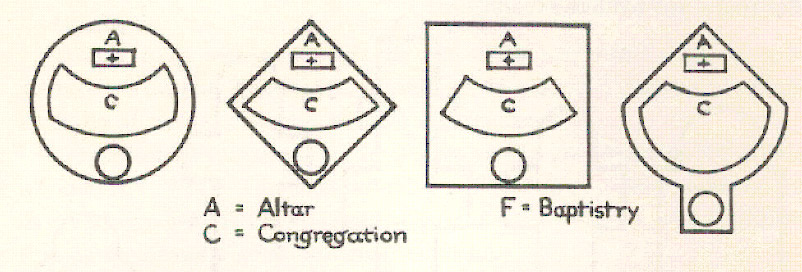

Which brings us to what Fr. Reinhold thinks a church should look like or "do." In answer, he offers the reader this [See below] - something he calls an "ideogram" of the ideal church. (Notice that the door is in the middle between the baptismal font and the main altar: that's Fr. Reinhold's ideologically preferred place.) Following this plan - this "ideogram" - will finally give us, he says, "suitable" liturgical architecture.

Now to be fair, and in the interests of full disclosure, I must immediately add that, according to Fr. Reinhold, this "ideogram" of the "suitable" church is not meant to be an actual "architectural design." Indeed, he says, "it could be built in Gothic, Renaissance, or Modern Style, if there were good reasons to decide to do so" (but, of course, the door would still need to be in the middle).

And yet, ironically enough, nowhere in his book does Fr. Reinhold offer us any "good reasons" to build new churches in anything like the Gothic or Renaissance styles. Indeed, in the conclusion of his book, he positively discourages it. He says of these older styles that they were "children of their own day," and that our architects "must find as good an expression in our language of form, as our fathers did in theirs."

Starting from Zero: Modern Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Modern Age

But this presupposition itself - that all the styles of the past were simply "children of their own day," which need to be replaced by a new, modern language of form that reflects our own age - shows as much as anything else Fr. Reinhold's distinctively Modernist cast of mind. It would have been completely foreign to a Medieval or Renaissance architect to talk this way. Quite the contrary. Medieval and Renaissance artists and architects saw themselves as working within a tradition - one whose standards they had to live up to. They didn't look back at the past with scorn and disdain as something passé, as something to be superceded; rather they looked at the great exemplars of the past with humility and pride as things to be emulated and imitated.

It was the Modernists, rather, who contrived the notion of re-creating architecture itself out of whole cloth, on a blank slate, so to speak, and who demanded an architecture that expressed the "spirit of the modern age." It was, for example, Mies van der Rohe, perhaps the most influential of all the Modernist architects, who had described architecture as "the will of the age conceived in spatial terms."

Whereas previous architects had always seen themselves as being in continuity with the great forms and architectural traditions of the past, the Modernists sought to throw off all those "chains" of the past and create architecture anew - from the ground up - much as Descartes had attempted to re-create philosophy by methodically doubting everything that had come before him and allowing back into his mind only those ideas that had mathematical clarity and certainty.

Author Tom Wolfe has written about those who studied in Germany's Bauhaus, for example, that:

The young architects and artists who came to the Bauhaus to live and study and learn from the Silver Prince [the Bauhaus's founder, Walter Gropius] talked about 'starting from zero.' One heard the phrase all the time: 'starting from zero.' ... how pure, how clean, how glorious it was to be ... starting from zero! ... So simple! So beautiful ... It was as if light had been let into one's dim brain for the first time. My God! - starting from zero! ... If you were young, it was wonderful stuff. Starting from zero referred to nothing less than re-creating the world.Just as, after Descartes, there no longer seemed to be any point in reading the likes of Plato or Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas, so too after Corbusier and Gropius, there no longer seemed to be any point in studying Vitruvius or Palladio or any of the work of the classical architects and designers. They were, quite literally, banned from the curriculum in favor of "starting from zero."And when those same architects fled from Hitler's Germany in the 1930's and ended up in America, they brought with them that same sensibility to the architectural schools in this country. Permit me, if you will, one more quotation from Tom Wolfe, in which he describes the somewhat unexpected character of this German "invasion":

All at once [says Wolfe], in 1937, the Silver Prince himself was here, in America. Walter Gropius; in person; in the flesh; and here to stay.... Other stars of the fabled Bauhaus arrived at about the same time: Breuer, Albers, Moholy-Nagy, Bayer, and Mies van der Rohe .... Here they came, uprooted, exhausted, penniless, men without a country, battered by fate ....As a refugee from a blighted land, [Gropius] would have been content with a friendly welcome, a place to lay his head, two or three meals a day until he could get on his own feet, a smile every once in a while, and a chance to work, if anybody needed him. And instead....Well, Gropius was made head of the school of architecture at Harvard, and Breuer joined him there. Moholy-Nagy opened the New Bauhaus, which evolved into the Chicago Institute of Design. Albers opened a rural Bauhaus in the hills of North Carolina, at Black Mountain College. [And Mies -] Mies was installed as dean of architecture at the Armour Institute of Chicago

And not just dean; master builder also. He was given a campus to create, twenty-one buildings in all, as the Armour Institute merged with the Lewis Institute to form the Illinois Institute of Technology. Twenty-one large buildings,

in the middle of the Depression, at a time when building had come almost to a halt in the United States - for an architect who had completed only seventeen buildings in his career - ...It was embarrassing, perhaps ... but it was the kind of thing one could learn to live with .... Within three years the course of American architecture had changed, utterly.... Everyone started from zero.So it was, I would suggest, that when specialists in liturgy, such as Fr. Reinhold, turned their minds to church architecture, they breathed in, as it were, "the spirit of the age": the currents of air that were wafting through all the American schools of architecture - perhaps without even being aware that that was what they were doing. But whether aware of it or not, when a liturgical specialist such as Fr. Reinhold thought about church architecture, it's clear that he thought about it in the categories that had been set by a generation of Modernist architects who, by the time he was writing and lecturing, controlled all the major schools of architecture in America. Indeed, this Modernist approach, I would argue, still dominates contemporary discussions about church architecture.

The Ideal Interior of the Modern Church

And indeed, Fr. Reinhold's modernist sensibilities affect not only his view of what is appropriate for the outside of the church, it influences his aesthetic judgments about interior design as well - and in ways that the contemporary church-goer will recognize instantly. Take, for example, the following statement about the "ideal parish church": "the ideal parish church," says Fr. Reinhold, "is the one in which the architecture creates the ideal setting for full participation." Now, the notion of "full and active participation" as a determining factor in church design is one that most people associate with Vatican II. But in fact, here it is being stated with authority already in 1947.

What is even more important to notice, however, is what Fr. Reinhold means when he talks about "the ideal setting for full participation." Note that, once again, instead of starting from a historical survey of excellent churches that have been shown to successfully encourage full and active participation, Fr. Reinhold, in line with his functionalist methodology, "starts from zero," so to speak - begins with a tabula rasa, as though no church had ever been built before - and derives his norms for proper functionalist design from his own conception of the "ideal" church. (And remember, by "ideal" here, we don't mean the design that has been shown by experience to be best or most practical, rather we mean, the design that is in accord with the proper aesthetic "ideal": that's the "ideal" church.)

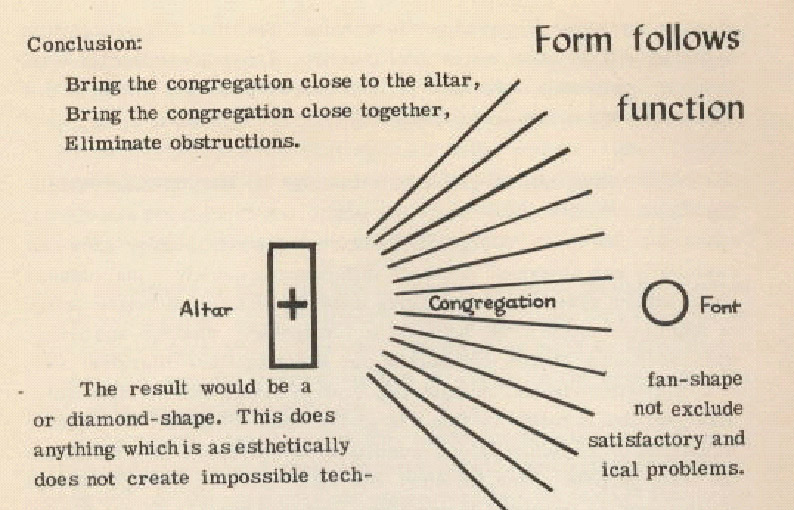

What, then, according to Fr. Reinhold, writing in 1947, is the "ideal setting for full participation"? Here it is (under that large, bold-faced heading that says "Form follows function"):

And here are some of possible configurations Fr. Reinhold suggests:

Ah yes, it's the fan-shaped congregation, or "church-in-the-round." You see it all the time.

Or perhaps I should say, you can hardly manage to escape it. In fact, liturgical "experts" have even taken regular straight churches and turned the congregation sideways to accomplish the "ideal" setting, which is "church-in-the -round."

Ever wonder why so many modern churches are built this way? Ever wonder why it seems impossible anymore to build a new church with straight aisles? Well, now you have your answer. This particular configuration (fan-shaped or "church-in-the-round") wasn't specified anywhere by the Second Vatican Council. And yet we find it stipulated here by an American liturgical "expert," as the necessary functional "form" for a church already in 1947 - nearly fifteen years before the Council!

What the Second Vatican Council did was wisely to exhort the faithful to "full and active participation" at the Mass. What seems to have happened, however, is that when American liturgical "experts" heard those words in 1965, they had already long been conditioned by their training to connect "full and active participation" with "fan-shaped" congregations and "church-in-the-round." And what's more, once connected, the two ideas became inseparable. To "go back," as they would put it, to straight aisles in a church would be tantamount to rejecting the Council's norms for "full and active participation." Indeed, it seems to have become impossible now for such experts to conceive of "full and active participation" without the fan-shaped, church-in-the-round design.

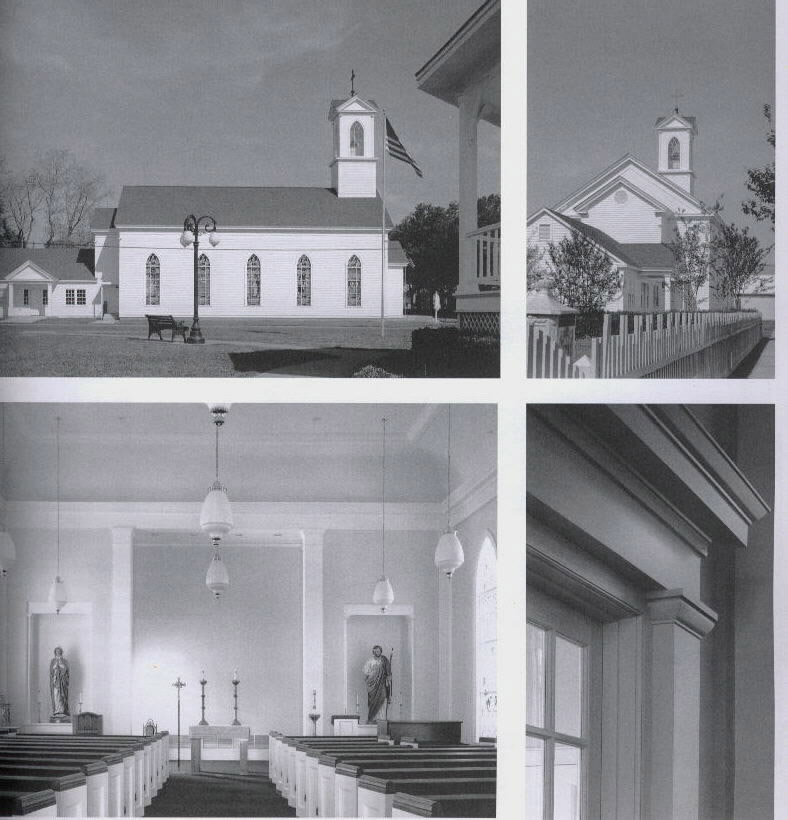

Indeed, not only is the fan-shaped, church-in-the-round design used all the time, it seems to have become a requirement. I found a remarkable example of this several years ago while I was leafing through a magazine called The Classicist. In volume 4 of that journal (pp. 36 and following), I found this picture of a lovely classic American church that had recently been built for a Catholic congregation in Jefferson, Texas [see below].

The picture shows a traditional structure which the architects had taken pains to ensure would fit nicely in with the ambience and the traditional architectural character of the town. But, having designed this beautiful exterior, the architects were then faced with a big problem on the interior. The article in The Classicist puts it this way:

The congregation, wishing to replace its building as soon as possible [after a fire], found that the liturgy had changed significantly since the Civil War. Contemporary liturgy often renders church architecture in the round [sic], a condition which presented a seemingly irreconcilable difference between religious requirements and the client's desires ... The result [namely, the final building plan] is a balance of the client's wish for a pre-Vatican II church and the new requirements in Catholic religious architecture.Now my first question upon reading this description was: When, pray tell, did the fan shape become a "religious requirement" in Catholic religious architecture? It may or may not be a good idea in any particular circumstance - but a requirement? The unfortunate result in this particular circumstance was that the architects - after they had designed this lovely, traditional church exterior - were then forced by ersatz "religious requirements" to turn the pews sideways on the inside.

They felt compelled, in other words, to "make the fan" - whether they wanted it or not. But quite frankly, in a church of this size - with no more than twelve pews total - it is unclear why anyone should have thought that "full and active participation" required fan-shaped seating - that is, other than the perception that this had become a "religious requirement" (although undoubtedly no one could have pointed to the actual canon requiring it, since there is none). What is really amazing about this story, moreover, is the fact that this modest, little church in an out-of-the-way town in Texas was so decisively effected by the architectural "ideal" of the fan-shaped design proposed over fifty years earlier by Fr. Reinhold (and others) that they considered it to be an absolute, unbending "requirement" of design for their new church. My, my, but ideas do have consequences.

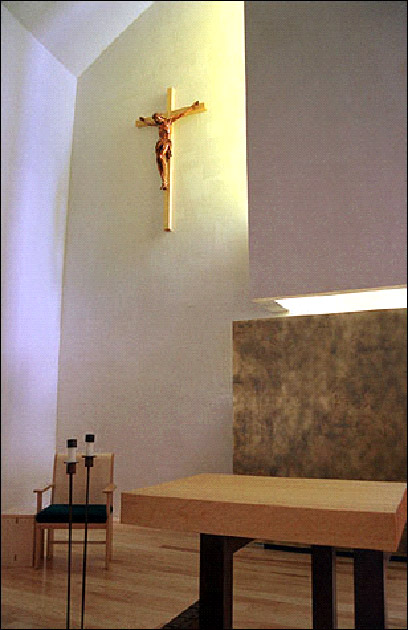

One last example: Indeed, if you'll look at the back wall of this little church [Slide 18], you'll notice another of the architectural innovations that people have mistakenly associated with the Council, but which was already present in 1947 in Fr. Reinhold's little book. See that blank, white wall? On p. 20 of his book, Fr. Reinhold mentions a wonderful new innovation he has discovered that he wishes to recommend to the reader: "Rudolf Schwarz proposes a white-washed wall behind the altar," says Fr. Reinhold. "There is great beauty in this original approach, but are we ready to carry it out?"

To that question, the answer, as subsequent history clearly shows, would have to be an emphatic "yes."

But now the question is: Can we ever get liturgical experts to stop? Indeed, must every church in Christendom [see below] have a blank, white-washed wall behind the altar? How many beautiful rear altars were torn out of older churches to make way for the miracle of the blank, white-washed wall behind the altar? It was Mies van der Rohe who said of modern architectural design, that "Less is more." Well, we've certainly gotten a lot more of the "less" than we ever thought we would!

The Upshot of All This

My point is simply this: Here in this 1947 treatise, we find a popular course of lectures proposing and promulgating to future liturgical experts the following notions: that a church should be understood as a covering or "skin" around a certain activity; that what takes primacy in building and designing a church is the Form or Idea of the "ideal church" which is to be applied; that the fan-shaped or "church-in-the-round" configuration is the "ideal" (thus required) design for achieving full participation; and that it would be preferred if we had the courage to require blank, white-washed walls. All this in 1947: long before the Second Vatican Council ever even began to set pen to paper.

Indeed, it is my contention that, when the Council documents finally did reach America in the mid-sixties, they were delivered into a social and cultural context that was already well-imbued with the modernist architectural ethos. And, moreover, when American liturgists read and interpreted those Counciliar documents, they did so, I would suggest, through the interpretive lense of that modernist architectural perspective. In short, we were well on our way to the kind of church set forth for our emulation in Environment and Art in Catholic Worship [see below] long before the Council fathers ever wrote a word of Sacrosanctum concilium.

This realization gives rise to the following considerations.

If what Fr. Reinhold proposes represents essentially a modernist approach to architecture, and if "modernism" is a style like any other style, then is it really wise to continue to canonize these principles as though they were essential to Catholic church architecture?

And if, as many cultural commentators have suggested, we are moving into a "post-modern" age - one that explicitly rejects the tenets of modernism - then will the churches that arise out of that modernist architectural ethos really continue to serve us well into the next generation? By their own modernist principles, modernist architects are supposed to design buildings that express the "spirit of the age." If the age is no longer modernist, then according to modernist principles, neither should the buildings be.

But more to the point, perhaps it's time we moved beyond several of the most basic tenets of modernism; and in particular, the notion that architecture must reflect the "spirit of the age" and that architecture should "start from zero." When it comes to Catholic church architecture, perhaps we should remember that the relevant "spirit of the age" is the saecula saeculorum, the "age of ages," or eternity. These are buildings that are meant to express the eternal in concrete, visible form. They are meant to be images of the heavenly city, places where we can enjoy a foretaste of the heavenly banquet enjoyed by all the saints and angels around the table of the Lord in saecula saeculorum.

And yet, by the sake token, church buildings are not - like God's revelation itself - things that remain outside of time and history; rather God's revelation enters into history. His grace has been present animating both our past and our future. We should build our churches with that sensibility in mind. Church architecture, like the liturgy itself, is something that has been received: it has been passed down to us over the generations. And we, in turn, are responsible for passing it on in the fullness of its integrity to the generations that come after our own. To insist that we must build churches that reflect the "spirit" of the present age, is to forsake the great architectural heritage that has been passed on to us by our forebears and to leave nothing of lasting value to the generations that come after. In my experience talking with students, nothing looks more dated and passé to them then buildings - especially church buildings - built in the 1960s and early '70s, or church buildings built more recently with that same style and sensibility. (One might make a similar comment about church music that was "hip" in the late '60s and early '70s. I'm not sure that many of the 50-something "boomers" who still valiantly belt out with guitar and tambourines the "Glory and Praise" songs of the St. Louis Jesuit's hey-day realize how thoroughly "out of it" they are with respect to the youth culture of today; although ostensibly we continue to sing such hymns "for the youth." And yet such hymns also don't offer anything especially "timeless" in their orientation or appeal. And thus what we are left with are pretty much just old, tired cultural relics of a fairly dull, unimaginative era.)

Thus if even post-modern architects have moved on beyond the strictures of architectural modernism, then perhaps the Catholic Church should as well. And indeed, since a new generation of post-modern architects have begun to re-introduce classical elements into their designs, might we not find ourselves presented with an exciting new opportunity [see below] to reintroduce them (and ourselves) to the inspiring beauty and magnificence of the Church's 2000-year heritage of great church architecture?

Lio Cases, project for Piazza Santa Croce, Rome, fall 1991

Michael Mesco, church in Chicago, IL, spring 1994

Laura Shea, St. Philip Neri, Chicago, Spring 1995

Thomas Michael Marano's entry in the design competition for the Cathedral of Los Angeles, fall 1996

To echo Fr. Reinhold's challenge: "There might be great beauty in this new approach. But are we ready to carry it out?"

NOTES

1. Steven J. Schloeder, Architecture in Communion: Implementing the Second Vatican Council through Liturgy and Architecture (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1998), 9.

2. Schloeder, 20.

3. Schloeder, 30.

4. Schloeder, 31. The final quotation, which Mr. Schloeder appears to be quoting as representing his own view, is taken from: C. Pickstone, "Creating Significant Space," Church Building (Autumn 1998): 10.

5. I think the writer means that Fr. Reinhold's name had become "a household word." See the "Foreword" by Fr. Michael Mathis, C.S.C. in H. A. Reinhold, Speaking of Liturgical Architecture (Notre Dame, IN: Univ. of Notre Dame Liturgical Programs, 1952). Indeed, more recently, Fr. Reinhold's "Timely Tracts" on liturgy in the journal Orate Fratres (later re-named Worship) have been described as being "at the forefront of the American liturgical movement from 1938 to 1954." On this, see How Firm a Foundation: Voices of the Early Liturgical Movement, compiled and introduced by Kathleen Hughes (Chicago, IL: Liturgy Training Publications, 1990), 206. Most of Fr. Reinhold's notable books involved the pre-Vatican II liturgy, e.g., The American Parish and the Roman Liturgy (1958), Bringing the Mass to the People (1960), and The Dynamics of the Liturgy (1961).

6. See the book's first foot-note; Speaking of Liturgical Architecture, 1 n.1. The influence on Catholic liturgy and worship in the U.S. of the liturgical summer schools held at Notre Dame after 1947 would be worthy of its own study.

7. Speaking of Liturgical Architecture, "Foreword" by Michael Mathis.

8. See "Functionalism" in Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th edition.

SPEAKING OF LITURGICAL ARCHITECTURE: Modernism and Modern Church Architecture | ESTHER: ORPHAN GIRL WHO BECAME QUEEN | KNOWING JESUS CHRIST | A 40 DAY JOURNEY OF DISCOVERY | THE GREATEST CRISIS IN THE CHRISTIAN LIFE | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

Randall Smith, Ph.D.

Department of Theology

University of St. Thomas

Houston, Texas 77006 E-mail: rsmith@stthom.edu